“If he was sitting in his car on the railroad tracks and the train was racing toward him, he would be in no hurry to move,” the Parkinson’s specialist said about me during our interview. Lisa was in the room and he was explaining my problem to her (although, given our almost eleven years together, she already knew me pretty well). In March of 2022, two years and seven months after my official diagnosis, I had been sent to the expert to get his opinion of my condition. Midway through our visit, I heard the question, “How does your Parkinson’s affect you?” and drew a blank. How could I not have answered that my right hand, while it tremored terribly at rest, was almost too clumsy to use in action; that I had formerly founded my hopes of a glorious gallery career on a therefore imperiled artistic ability; or that I worried that my talent had already gone to waste as I had fallen prey to premature degeneration? Instead, I stalled.

The doctor –– technically, he’s a physician’s assistant –– claimed that my ambivalence was due to the disease. Ambivalence sounded right, I agreed. After later looking it up to be sure, I learned that the word actually means “a state of having mixed feelings or contradictory ideas.” Apathy is, on the other hand, what I had assumed that he had meant. It’s a “lack of feeling or emotion, interest or concern.” In the scenario that started me thinking, where I was about to let a locomotive plow into my car, I had seemed more unconcerned than conflicted.

Indifferent or equivocal, which am I: one, neither or both?

Parkinson’s Disease results from a dopamine deficit. That’s the chemical that motivates you to either avoid or achieve a certain outcome. It acts like a messenger in your central nervous system and, without it, things don’t work so well. Motor control, cognitive and behavioral issues are common, apathy among them. So that explains why I might have seemed listless these past few years. Having yet to reach fifty when I got the news that I had PD, my affliction is considered “early onset.” Still, some of what I am describing are life-long symptoms. The clinical story doesn’t account for the previous forty-nine years.

Over two decades ago, for example, my second wife introduced me to a friend of hers whom I overheard say about me, “If he were any calmer, he’d be dead.” My attempts at humor have always amounted to making the most ridiculous statements with a totally straight face (what the doctors call a “flat affect” or “masked expression” –– a lot of people think that I’m being serious, and that I’m an idiot, whereas others get the joke). I was even chided as a child for not getting more excited. My dad drove me to a model railroad show in the city, once. It took up all of a Saturday afternoon and he got upset that I wasn’t having any fun. I was actually having the time of my life and was surprised to learn that I looked miserable.

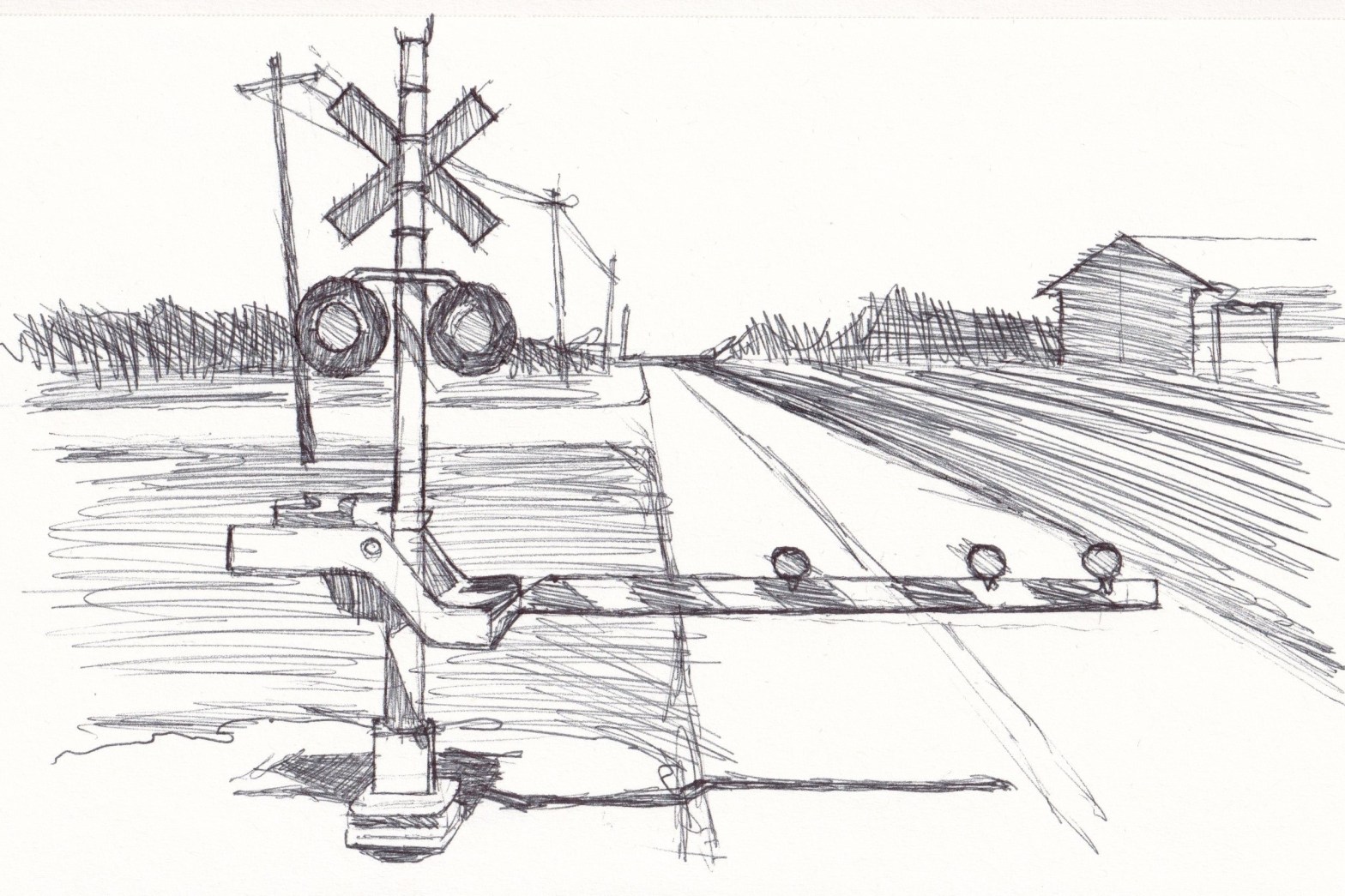

The last episode is appropriate to illustrate a point (and not just because, with the initial analogy yet to be resolved, I am still parked on the tracks while letting a train thunder my way). My grandfather, on my mother’s side, was a railroad enthusiast. Whenever my family and I left our hilltop home in Northern California to visit the Los Angeles area, we’d stop by their house, I would go to the den and study his collection of HO scale brass locomotives. They were collector’s pieces and displayed, as such, in a case mounted on the wall. When I expressed an interest, Gramps loaded me up with some of his old magazines on the subject. Back at home, my dad built a sturdy table in my bedroom. It supported a four-by-seven-foot sheet of plywood that could have hosted a miniature world complete with tiny buildings, mountains and bridges … but didn’t. Instead, it remained a bare board for the length of my early adolescence. So my noncommittal attitude, at least at an early age, wasn’t only a matter of appearances: I must not have cared. My apathy is deeply seeded. Incidentally, I sometimes wonder if the scenes that I depict in my art aren’t attempts at constructing the countryside that I had failed to craft as a boy.

Even so, I spent hours dreaming up how to proceed with the train layout in my bedroom that never got off the ground. After Gramps got me a subscription to a model railroad publication, pouring over the periodical took up a lot of my time. I can’t really say that I didn’t care. A few years later, I even made another attempt, started a smaller project and eventually pawned it off on my poor little niece long before it was finished. Admittedly, most kids aren’t too big on follow-through. Desire wasn’t the problem, though. My personality flaw arose where the rubber meets the road.

That figure of speech brings me back to my impending (and so-far only symbolic) annihilation. My tires straddle the tracks along which a massive engine is pulling a mile-long train of boxcars, gondolas and hoppers –– the kind that you know would take forever to stop –– in my direction at an almost recklessly treacherous speed. The blaring horn announces my doom while I’m pondering whether ambivalence or apathy keeps me from acting. I blame a busy mental life for my indecision. Albeit overdramatic, it’s a fitting anecdote. While I contemplate what I should do, the seconds are ticking away. Presently, there are steps that I can take (one involves a brain implant; the possibility had prompted my appointment with the specialist who remarked on my vacillation while I was evaluated as a candidate) to improve the grim reality that awaits me. Although it isn’t as simple as shifting into gear, releasing the brake and pressing the gas pedal of a car inexplicably parked in a railroad crossing, it also isn’t as insurmountable as I have imagined for many months. Starting with a metaphor that’s uniquely automotive, it doesn’t matter where I steer so long as I move forward. Am I trapped between the gates? Will I need to bust one arm apart to escape a far more deadly collision? However I got here, it’s messy way to begin a road trip (or the record of one, at any rate).